Solving The Apathy Problem: How Achievement Leads to Motivation

First, let me say that apathy is a big problem. It is something I'm seeing while working in classrooms with students, something that teachers I'm working with are talking about, and even though apathy has always been an issue...it feels like it may be different right now.

If you are working in schools or at the university level, you’ve been no doubt dealing with it as well. There are countless studies, articles, and editorials on the issues of apathy but not many solutions are in place.

In this video, I go deep into some of the reasons for the rise in apathy, and how we can combat it in the classroom.

However, there is one big piece missing that I’d like to focus on in addition to the three strategies shared in the video. Let’s dive in.

The Relationship Between Apathy, Motivation, and Achievement

Early on in my teaching career, I focused most of my attention on covering curriculum, hitting standards, and providing a rigorous and challenging learning environment.

Students called me a “tough teacher” and “hard grader”. I believed this was the best path to raising the bar and helping my students be successful.

A few wrenches ruined this plan in my early years of teaching.

First, I was teaching most of my students in the same way, and while many rose to the occasion, there were others who were completely turned off by this type of teaching. At first I kept the “tough teacher” act going, but eventually I wore down. I wasn’t reaching some of my students, and I had myself to blame for much of it.

Second, the focus on achievement and success of tests and papers, was centered on the belief that my students really wanted to get A’s. Turns out some of them did, and they would try really hard to move that “B” up to an “A”.

Also, as my veteran colleagues tried to tell me, some students did not care about getting that ‘A’. Many were done playing the game of school, while others were playing the game just to “Pass” or to get a “B” to keep their parents happy.

Finally, my class felt like another cog in the game of school. It wasn’t too rewarding on my end to teach students who were (at best) compliant, and it was not rewarding for all the students in my class who were not at the top of the bell curve.

Every time I would hand out an assignment, my students would ask, “How many points is this worth Mr.J?”

“If I turn it in a day late how many points off?”

“Do we have extra credit options if we get a bad grade?”

And so on…

Something had to give.

I tell this story often when I’m working with groups. I was in a frustrated and desperate place as a teacher. I turned into a complainer. I did not understand why my students would not conform to the way I had set up my classroom and all “care” about what we were learning about.

I contemplated leaving the profession, but coaching football and lacrosse kept me grounded in the work.

This is when I found the work of Daniel Pink (Drive) and went all-in on intrinsic motivation with my students during the second half of the year. We did 20% Time (Genius Hour ) projects and the results were incredible.

Not only were my students challenged to stop playing the “game of school”, but I was as well.

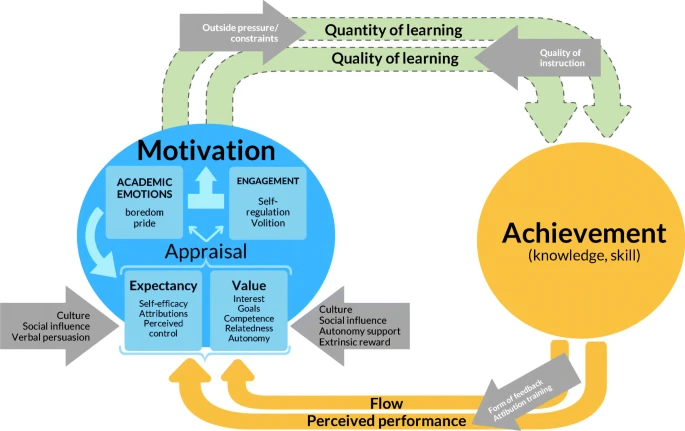

It was tough to put into words what I felt as a teacher, but this flow chart sums it up almost perfectly (from an amazing Literature Review on the research).

Fig 1

My students felt the academic emotion of “pride” in their work. They also had to practice “self-regulation” as they had “perceived control” of the process.

Their values were met through “interest” and “autonomy” while they set their own “goals” for learning.

All of this created a real sense of motivation.

You can see in the flow chart that the feeling of motivation then leads to the quantity and quality of learning.

They spent more time on their 20% time projects than anything we had done before. They were committed to the process even when things didn’t go right the first time, and shared their epic fails along the way.

A Quick Aside on Quantity and Quality of Learning

“Quality of learning” is what I often question as a teacher when discussing inquiry-based and project-based learning. However, I’m reminded of the story of a pottery teacher.

The pottery teacher gave her students a goal to create the most perfectly shaped cup by the end of the semester. Half the class was tasked with working to refine and try to create this perfect cup (quality focus), while the other half of the class was tasked with creating as many cups as possible during the semester (quantity focus).

At the end of the semester, which group do you think came the closest to the perfect cup?

The quantity group by far! The act of creating over and over again led to higher levels of achievement.

This is what I saw with my students.

A Missing Piece to Motivation

This all seems great, in theory. But, what if you don’t have the freedom or autonomy to allow students choice and voice all the time (most of us don’t)?

What if students are so checked out of school, that they don’t even get excited about learning something they “want to learn” and seemingly have no interests (this happened to me all the time with Genius Hour)?

Simply put, what if students do not feel intrinsically motivated? What can we do?

Well, this happens all the time. It has happened to me as a learner and probably you as well.

I remember doing extremely well on my addition, subtraction, and multiplication timetables. At this point in my academic career, I enjoyed Math, had fun playing games like “24” in class, and never truly questioned my abilities.

Then came division. I struggled on the first timetables test. Struggled on the second as well.

Then came fractions. I was lost. My motivation for math dropped. I doubled down as “reader” and thought much less of myself as a math student.

Then, something interesting happened in high school. My Algebra 2 teacher wanted me to take his Computer Programming class along with Trig the following year. He said that even though I got some questions wrong, he loved the way my thinking looked on paper as I worked through the problems, and though it would serve me well in Computer Programming.

The following school year, I loved the Programming class. I spent extra time before and after school working through the math needed to program C++ to do what I wanted it to do to create all kinds of games and simulations.

In this case, the motivation did not lead to achievement. Instead, my perceived view of achievement led to motivation (one situation it was negative and the other it was positive). We can see how this works from the flow chart below, both achievement and motivation have a reciprocal effect on each other.

Fig 2

We see this happen in sports all the time. Win a few games and your team is much more likely to be motivated to practice. Score a goal, and you feel like you want to spend extra time getting better. Have a few plays go your way in a game, feel motivated to try and complete a come back.

The “aha” moment for me was this: Achievement can also lead to motivation.

The Research Between Motivation and Achievement

If you are as interested in this topic as I am, go ahead and read this entire review: Motivation-Achievement Cycles in Learning: a Literature Review and Research Agenda - it is well worth the time to dig into some of the research and also see the limitations on these types of studies.

Here is one of the main highlights about the connection between motivation and achievement:

Our discussion of various theories of motivation in education showed how densely motivation and performance are interlinked. They can best be seen as a cycle of mutually reinforcing relations. While a cycle suggests a closed loop, we list several options for outside intervention, which are represented by the gray arrows in Fig. 1. Some of these are well-researched practical interventions, such as autonomy support and training in helpful attributions (Hulleman et al., 2010). Others are excellent avenues for future research. For example, designing how feedback reaches the learner offers opportunities for motivation support. Research has shown how to provide negative feedback in a way that does not lower a learner’s motivation (Fong et al., 2019), how peer comparison can be harnessed for motivation (Mumm & Mutlu, 2011), or how feedback can be given without giving away that errors have been made (Narciss & Huth, 2006). It is our impression that this research has so far not reached all classrooms.

Has it reached your classrooms? When a student has perceived achievement in a classroom, on a playing field, or in an extra curricular they are more likely to be motivated to continue learning, or practicing, or trying!

Of course, students are going to be apathetic if they feel like they’ve already lost at the game of school.

And, of course, students are going to be apathetic if they have a perceived low level of achievement (even when they’ve tried their best in the past).

I’m reminded of this video I’ve shared in many of my presentations. How can we give students a “1480 moment” during their time in school?

Does this work every time? Of course not.

Is the research full developed? No, as you can see below there is much to be discovered.

In conclusion, this view of a cycle between motivation and achievement, as shown in Fig. 1, has intuitive appeal and fits well with theories of academic motivation. However, empirical evidence for a cycle is far from complete. The research agenda we have presented contains important challenges for future research aimed at elucidating how motivation and achievement exactly interact, and whether a cycle and a network of constructs are good ways of conceptualizing these interactions. As academic motivation typically drops considerably in adolescence and may be lower for some groups (e.g., through the effects of SES, stereotype threat, and the likes), such evidence is necessary for gaining knowledge on how to best intervene in the cycle, and bring out the best in each student.

And yet, I’ve seen it with my own eyes. As a teacher, coach, and school leader I know that achievement leads to motivation, and that motivation leads to achievement.

When we are dealing with students (and maybe even colleagues) that are struggling with apathy — maybe the first step is not to increase “motivation”, but instead" find some moments where “achievement” can take place and change the cycle of behavior moving forward.