Let’s focus on AI-Fluency, not AI-Literacy.

K-12 right now is full of new “AI words.”

AI-Literacy. AI-Readiness. AI skills. AI competencies.

Here’s my issue, and an argument for you as a school leader:

AI-literacy is an overloaded, still-fuzzy buzzword that risks distracting us from the real literacy crisis (reading, writing, critical comprehension).

AI-fluency is a better target. Students and educators who can actually work with AI in authentic tasks, grounded in strong foundational literacy.

Let’s unpack the difference, and why your professional learning and strategic plan should use “AI-fluency,” not “AI-literacy,” as the north star.

We already have a literacy crisis. Let’s not water that word down.

Before we add another “literacy,” look at where we are with the original ones.

On the 2024 NAEP, reading scores for 4th and 8th graders fell again, continuing a steady decline that predates COVID.

9 year old students saw the largest reading score drop since 1990 between 2020 and 2022.

These declines are steepest for our lowest-performing students, widening gaps between top and bottom quartiles.

At the same time, UNESCO’s global guidance on generative AI emphasizes that foundational literacy, numeracy, and scientific literacy “will remain key for education in the future.”

In other words:

Kids still need to read deeply, write clearly, and think critically (maybe more than ever) in an AI-saturated world.

So when we casually slap “AI-literacy” next to reading and writing, we risk two big things.

Confusing parents and boards about what “literacy” even means

Pulling attention and resources away from the very thing AI depends on: students who can read, comprehend, and judge information

We don’t need another literacy. We need to keep literacy sacred and ask: How does AI help us build it?

Note: There are already some amazing tools like Mentava, Ello, and Microsoft Reading Coach that are helping in these areas.

AI-literacy is a fuzzy construct that isn’t “real” like reading literacy

If you look at the research on AI-literacy, one thing stands out: no one agrees what it actually is.

A 2021 scoping review of AI-literacy research found that definitions vary widely and that there is “not yet a single, broadly agreed-upon definition.”

Recent frameworks from Digital Promise, UNESCO, and the OECD/European Commission describe AI-literacy as a mix of:

Basic understanding of how AI works

Ability to critically evaluate AI systems

Awareness of ethics, bias, and social impact

Those are good goals. But notice what’s happening (it’s confusing).

We’re calling a bundle of knowledge, attitudes, and critical thinking “AI-literacy” even though they’re built on existing “literacies such as digital literacy, data literacy, media literacy, and plain old reading comprehension.

The field itself says it’s still emerging and context-specific, not a stable, testable construct like reading literacy.

So when you see “AI-literacy” in policy docs, PD slides, or vendor pitches, remember:

AI-literacy is real in the sense that people use the term; it is not real in the sense of being a coherent, settled skill domain like reading literacy.

If we elevate AI-literacy to the same level as reading or math literacy, especially in K-8, we risk creating new “AI-literacy” checklists instead of improving reading and writing instruction.

We’ll waste time adding another siloed initiative rather than integrating AI into what we already do.

And, on top of all that, we’ll continue to confuse teachers with overlapping frameworks: digital literacy, media literacy, AI literacy, data literacy, information literacy…

You don’t need another literacy initiative. You need a clear vision of how AI supports the literacy you already care about.

Here’s why AI-fluency is a better target for schools.

Now contrast that with how emerging research and practice define AI-fluency.

Ohio State University’s AI Fluency initiative, for example, defines AI fluency as graduates having:

“deep expertise in their field and the ability to apply AI thoughtfully, responsibly, and innovatively within it,”

becoming “bilingual—fluent in both their discipline and the responsible, intuitive use of AI.”

Other definitions from higher ed, industry, and workforce research emphasize that AI-fluency means you can:

Work effectively with AI tools in authentic tasks

Understand both capabilities and limitations

Exercise critical judgment, ethical reasoning, and creativity with AI in your domain

One recent analysis from Harvard Business Publishing on AI-fluent employees found that fluency is built through hands-on experimentation, not theory: people learn by repeatedly using AI in their real work, reflecting, and adjusting.That’s a game-changer for K-12.

AI-fluency = applied, situated, iterative problem-solving with AI in context.

And most importantly, you cannot be AI-fluent if you can’t do these basic skills.

Can’t read a long passage closely

Can’t distinguish a good argument from a bad one

Can’t write clearly enough to prompt, revise, and communicate outcomes

AI-fluency depends on literacy. It doesn’t replace it.

What AI-fluency looks like in K-12 (without inventing a new subject)

So if you drop “AI-literacy” as a label, what does an AI-fluent school actually do?

A. Keep literacy sacred and use AI to strengthen it

Use generative AI to give students more feedback on writing, more often, under teacher guidance. (UNESCO explicitly calls for AI to support, but not replace, human teachers in this way.)

Have students critique AI-generated texts. Spend time to fact-check, identify bias, compare style, and then revise, strengthening close reading and argumentation. Here’s a good starting point of why this matters.

Use AI to differentiate reading passages (Lexile, background knowledge, language support) while keeping teacher-selected, complex anchor texts at the center.

Literacy is still the goal. AI is the scaffold.

B. Build AI-fluency through authentic tasks, not separate “AI lessons”

In ELA: Students use AI to brainstorm thesis statements, then manually draft and revise an essay. They’ll spend time comparing their work with AI’s and defending their choices.

In math: Students use AI to generate multiple solution paths to the same problem and critique the reasoning.

In CTE: Students use AI to simulate client briefs, write technical documentation, or prototype designs. Then discuss the best path and why.

This aligns with emerging AI-fluency programs in higher ed and industry, which emphasize domain-specific application over generic tool tours.

C. Teach AI ethics and critical use as extensions of existing literacies

Rather than a new “AI-literacy” unit, we should do the following:

Embed AI bias analysis into media literacy lessons.

Integrate AI-related case studies into digital citizenship.

Use AI examples when teaching source evaluation, data privacy, and online safety.

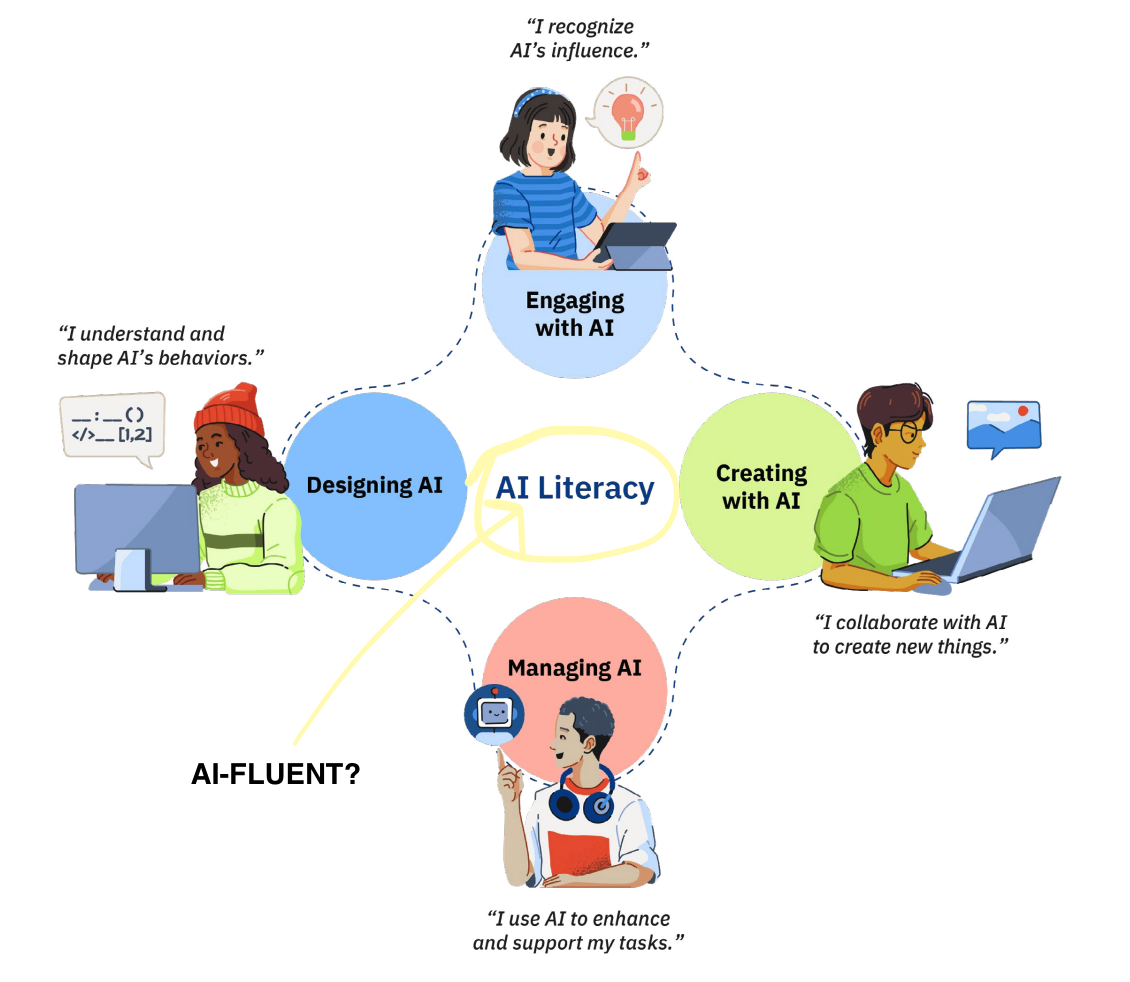

You’re not inventing a new literacy, you’re updating the contexts where existing literacies are practiced. I wish this graphic from the OECD and European Commission had AI-Fluent in the middle because it sums up what we are talking about here:

A practical roadmap for school leaders: From AI-literacy to AI-fluency

If you’re updating your strategic plan, profile of a graduate, or tech/future vision, here’s a straightforward shift.

Step 1: Clean up your language

Avoid: “All students will develop AI-literacy by 2027.”

Use instead: “All students will develop AI-fluency, which we will define as the ability to use AI tools thoughtfully, responsibly, and creatively to support learning, grounded in strong reading, writing, and critical thinking skills.”

This mirrors how leading frameworks (Ohio St, Ringling College of Art and Design, and more in this Forbes piece) describe AI-fluency while keeping foundational literacy front and center.

Step 2: Anchor AI-fluency in your existing priorities

Tie AI-fluency goals explicitly to reading improvement plans (NAEP gap closing, state assessments), writing across the curriculum, and existing digital citizenship/media literacy standards.

And use UNESCO/OECD guidance to show that global policy bodies are telling us to protect foundational literacy while integrating AI, not replace it.

Step 3: Design PD around “working with AI,” not “learning about AI”

Your PD should help teachers co-plan lessons where students use AI as a thinking partner (brainstorm → critique → refine). Help them set clear classroom norms and guardrails, as well as evaluate AI tools against your data privacy and equity commitments.

This matches what workforce leaders are calling for over and over again. They are looking for young people who have hands-on experience “working out” with AI tools, not just theoretical knowledge about how they function.

Step 4: Use resources that center fluency

Rather than generic “AI-literacy slides,” look for or adapt AI-fluency courses that focus on delegation, discernment, and responsible use in real tasks, like Anthropic’s free AI Fluency course for families and students.

You can also can reimagine frameworks and reinterpret through a fluency lens, such as the OECD/EC AILit framework (knowledge + skills + attitudes for navigating AI) and Digital Promise’s AI-literacy resources (critical understanding and use).

Position them in your district as tools to support fluency in context, not a separate “AI-literacy” strand.

Let’s stop chasing AI-literacy. Instead, let’s build AI-fluent, deeply literate learners.

Here’s the bottom line I’d put in front of your board, cabinet, or leadership team:

We are in a genuine literacy crisis. Reading scores and reading stamina are declining, especially for our most vulnerable students.

The term “AI-literacy” is still an emerging, undefined construct. It overlaps heavily with existing literacies and is not comparable to reading literacy as a stable, assessed domain.

Global guidance is clear: foundational literacy and numeracy remain non-negotiable, even as AI becomes ubiquitous.

AI-fluency offers a clearer, more actionable goal: students and educators who can use AI well in authentic learning and work, grounded in strong reading, writing, and critical thinking.

So, if you’re a K-12 leader, here’s your move:

Retire “AI-literacy” as a headline goal. Use it, if at all, only as a supporting idea within broader digital and media literacy.

Elevate “AI-fluency” as your guiding phrase. Define it locally as the ability to collaborate with AI to read, write, think, and create at higher levels.

Publicly recommit to foundational literacy. Make it crystal clear to your community: AI is here to strengthenreading and writing, not compete with them.

Design your PD, curriculum pilots, and policies around AI-fluency in context inside real tasks, real classes, real problems.

Your students don’t need to pass an “AI-literacy test.”

They need to read well enough, think deeply enough, and write clearly enough to be empowered in the best possible way, with or without AI at their side.